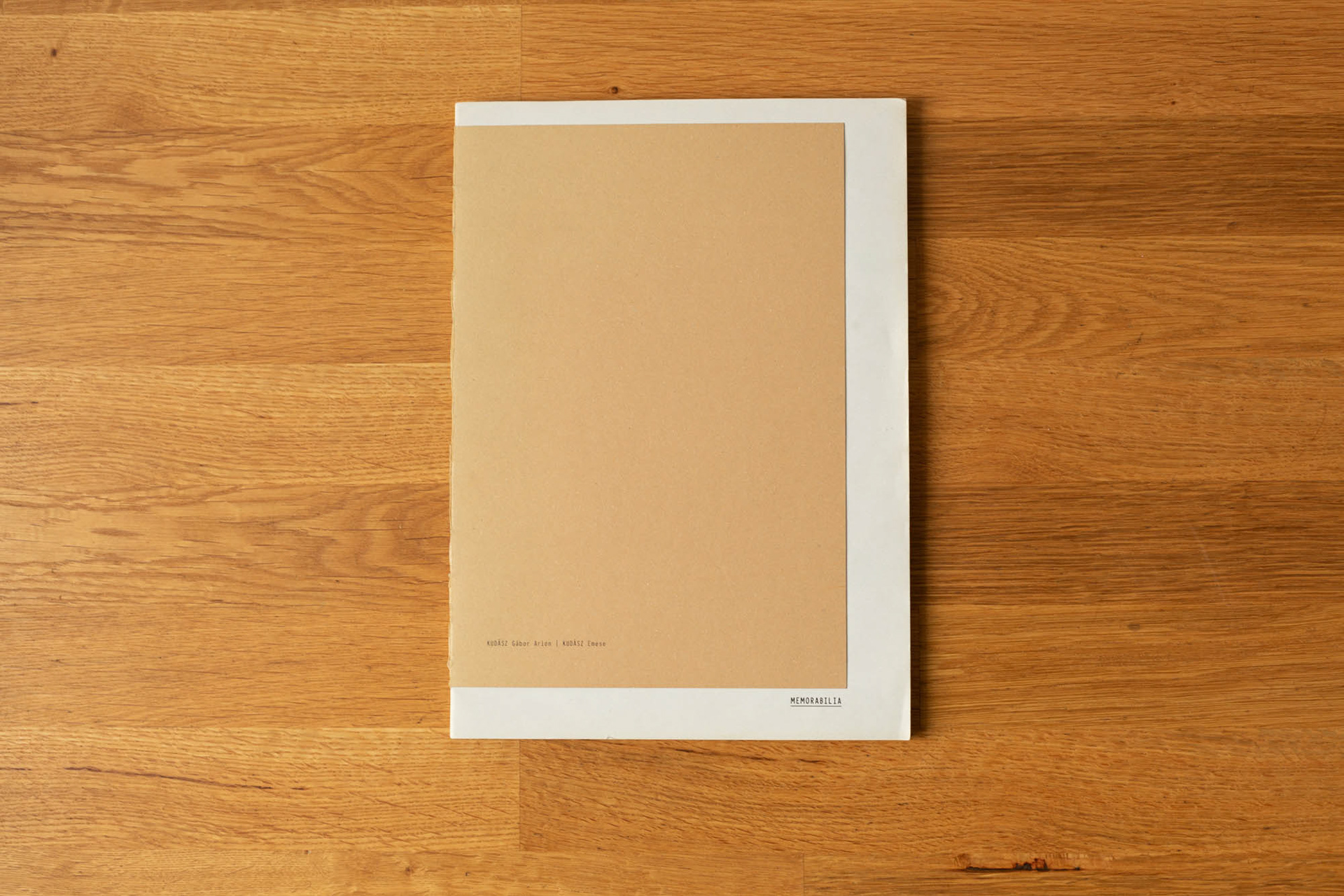

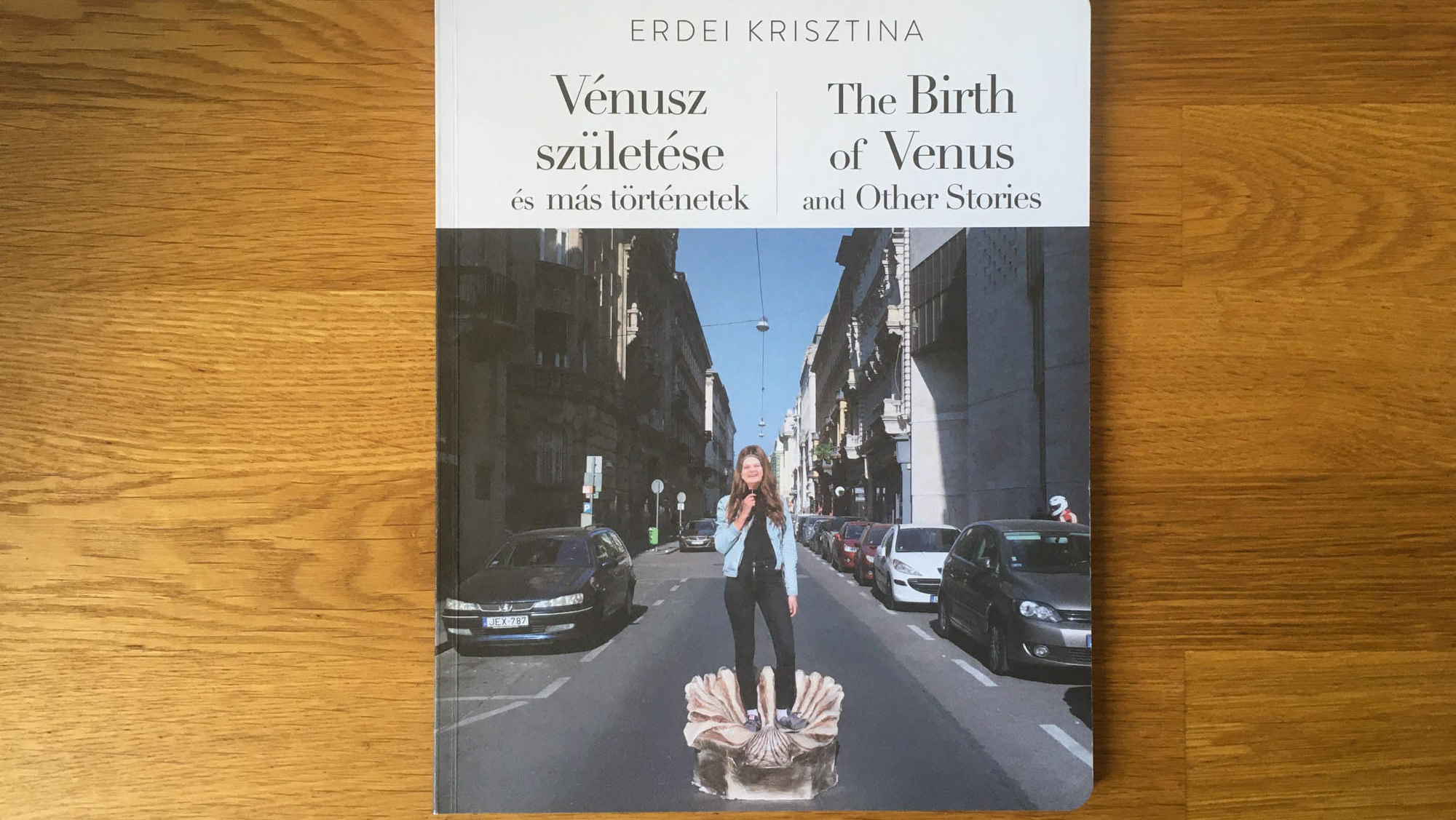

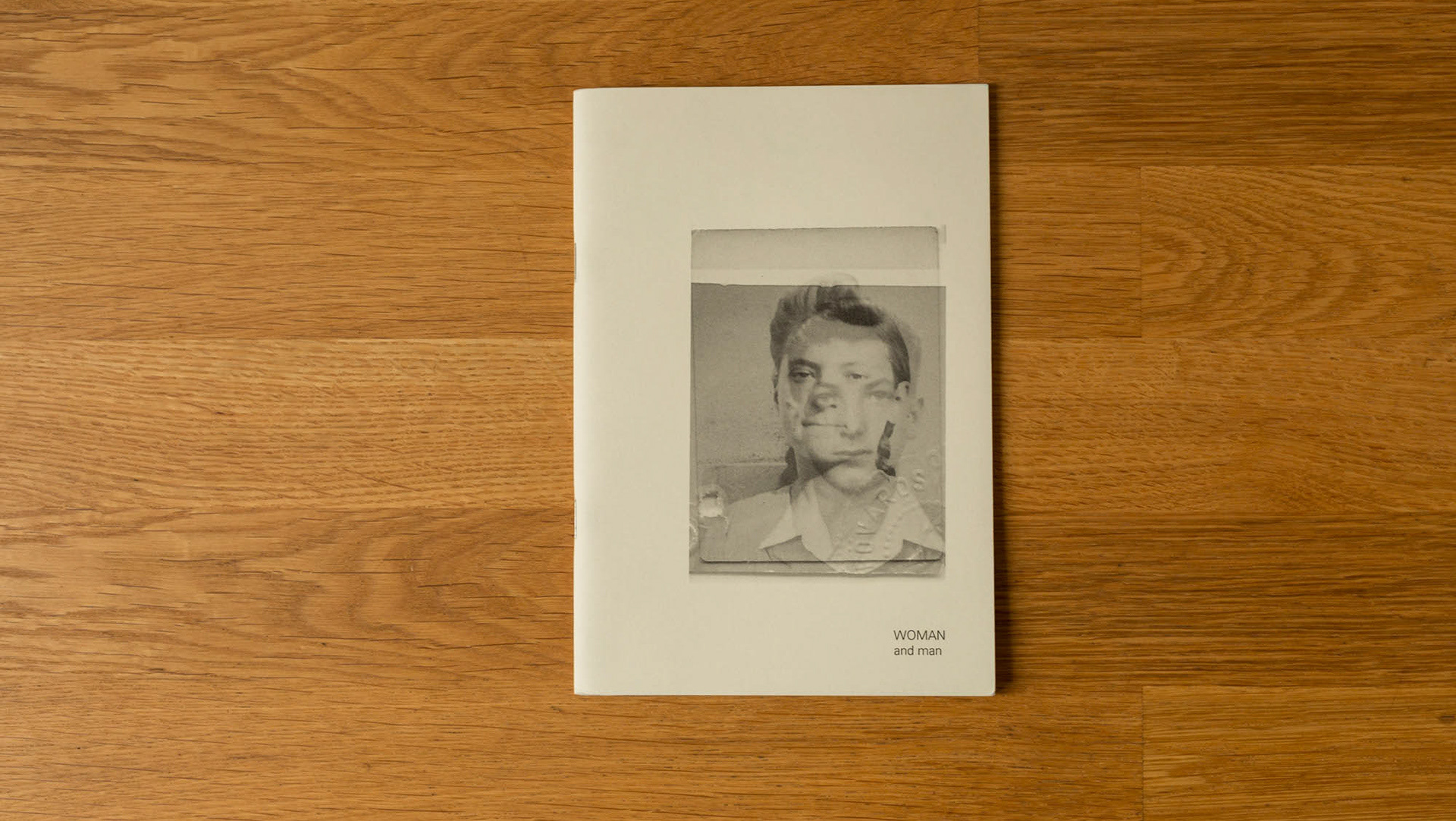

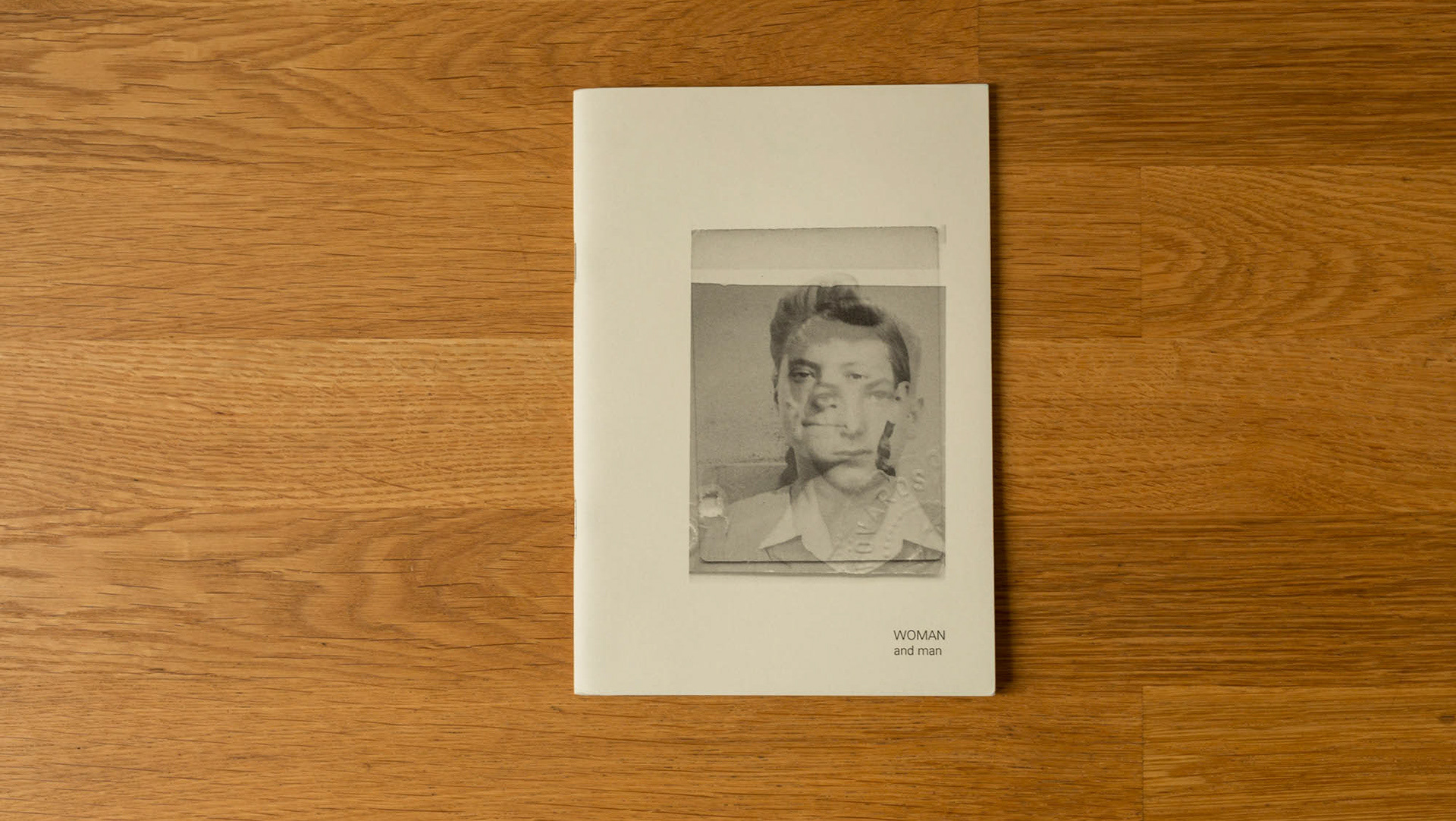

Gábor Arion KUDÁSZ, Memorabilia

Artist: Gábor Arion KUDÁSZ

Title: Memorabilia

Text: Gabriella Uhl (English and Hungarian)

Designer: Nora Demeczky

Editor: Gábor Arion KUDÁSZ

Publisher: Published in collaboration of Hungarian House of Photography and Faur Zsófi Gallery in 300 copies

Publication date and place: 2014, Budapest

Format, binding: 20x28cm Soft cover Stiffcover book, sewn naked binding, four-color lithography

Number of pages and images: 184 pages, 150 black and white photographs

Edition: 300

Type of printing and paper: offset

Genre: Photobook

Book description (eng):

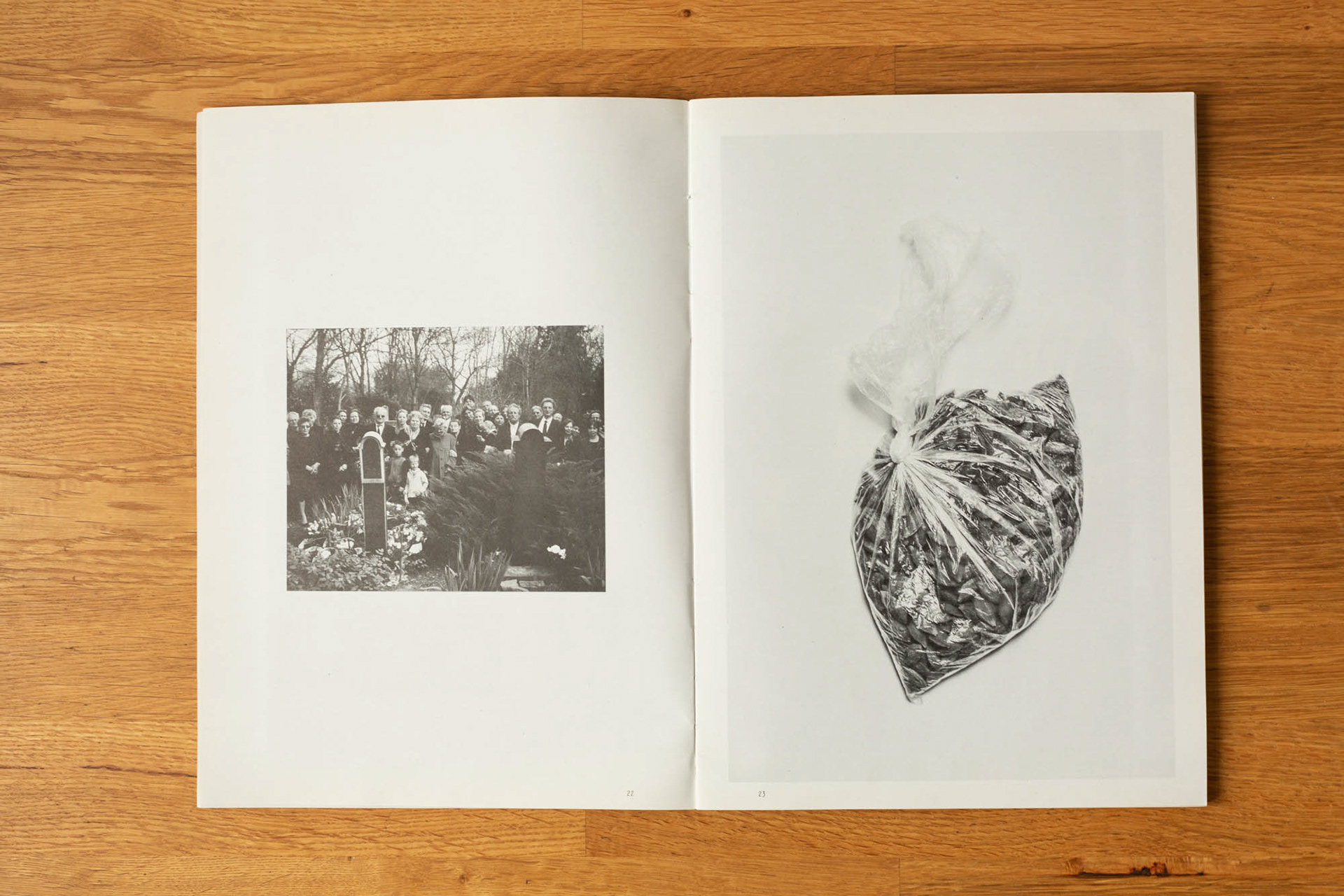

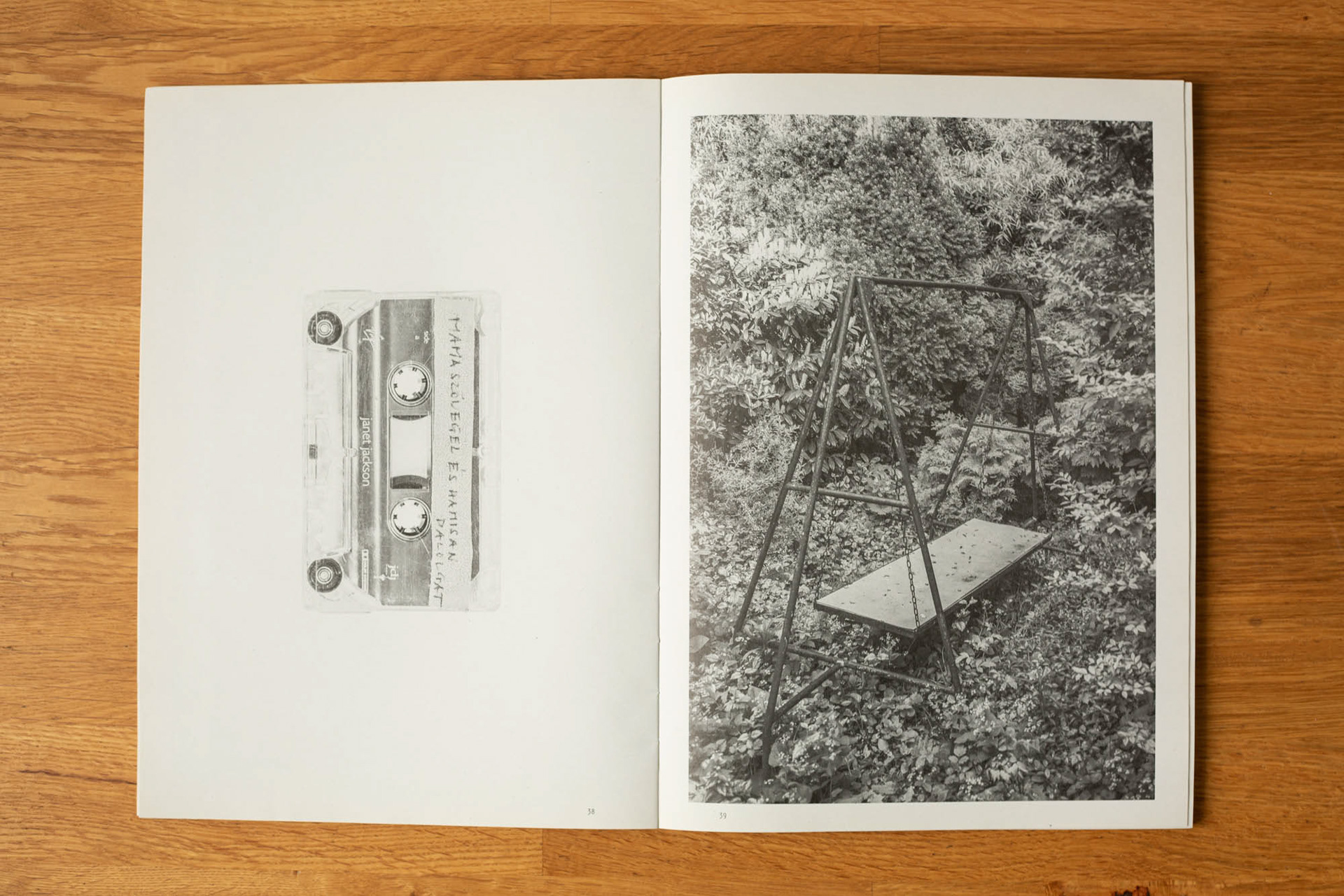

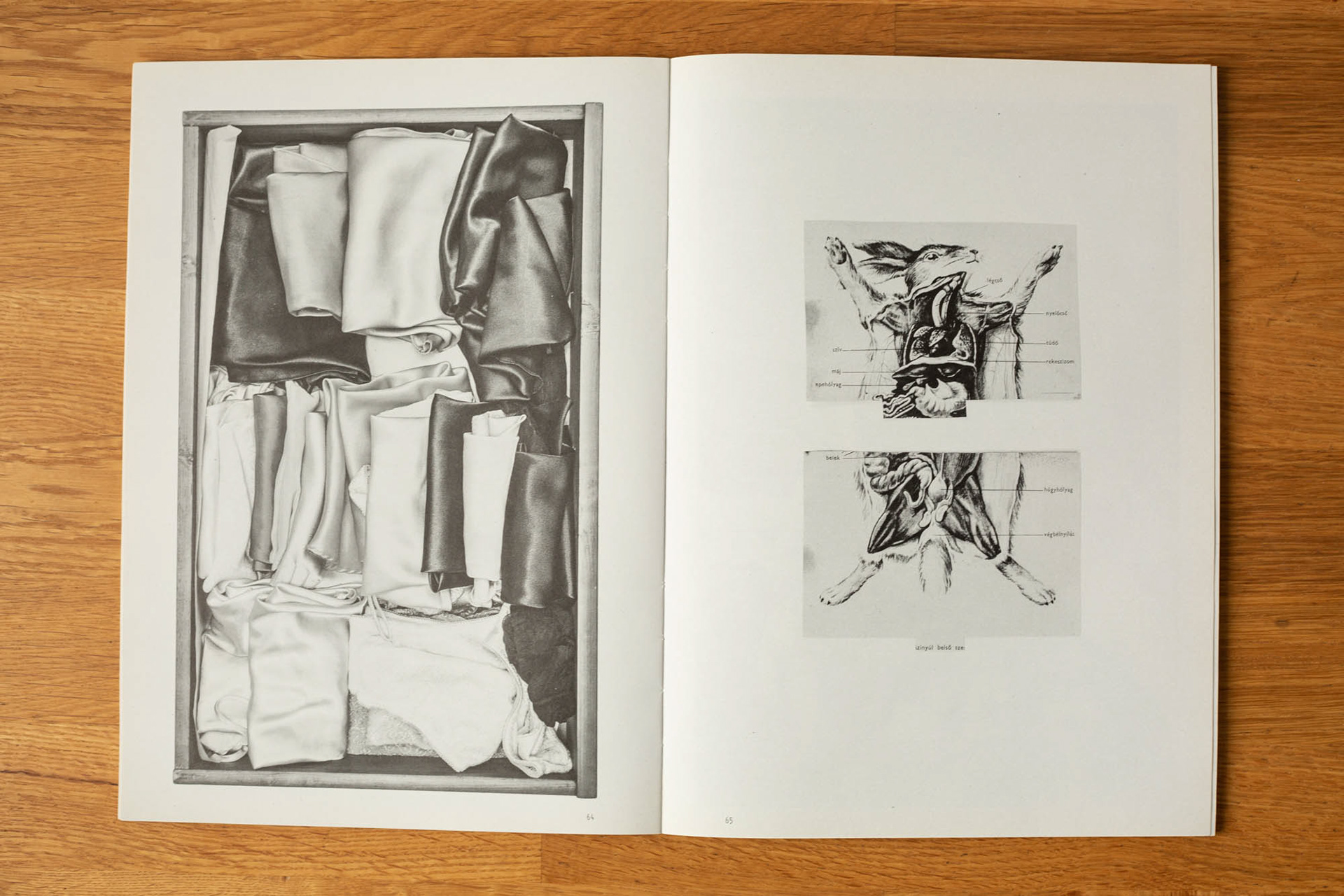

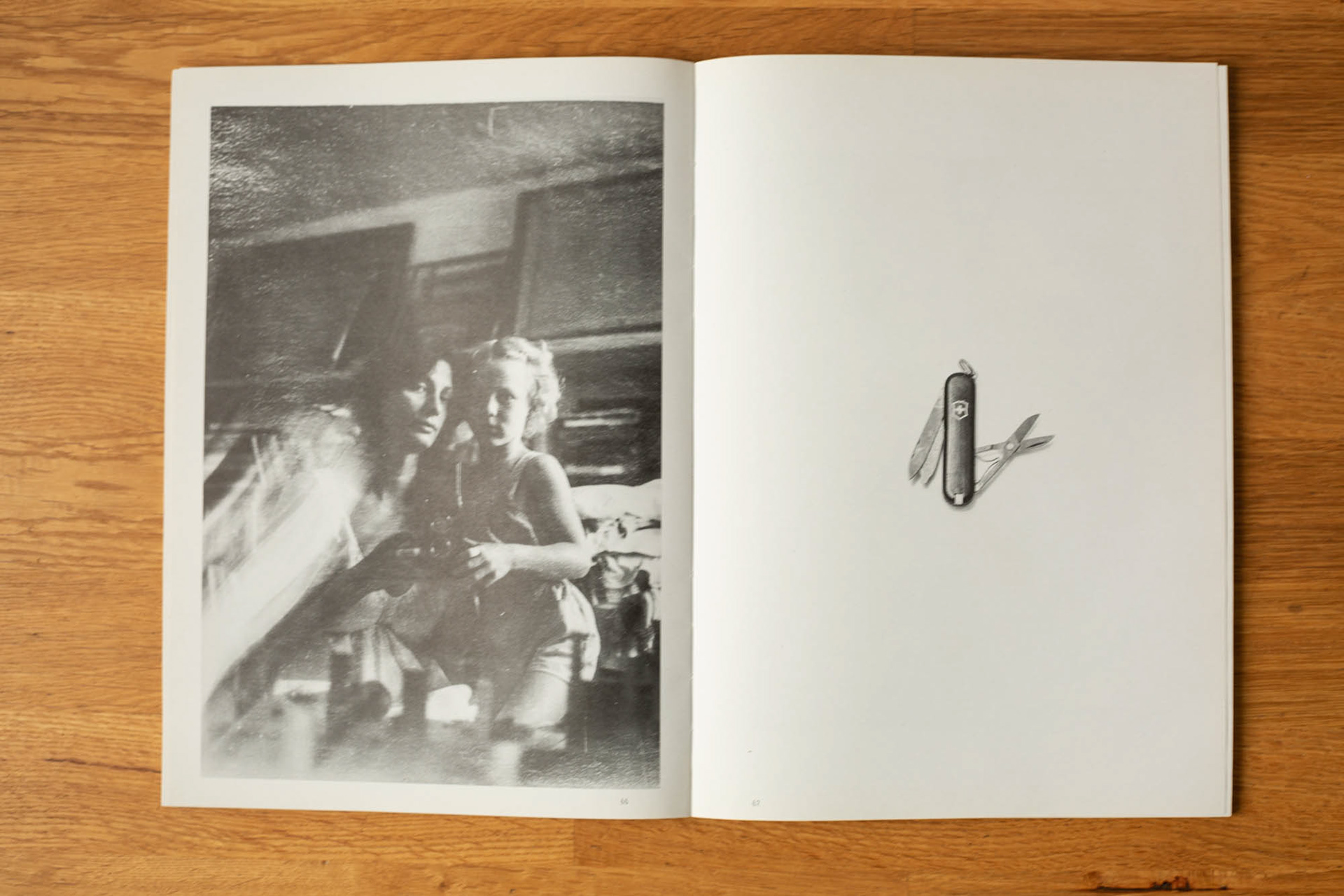

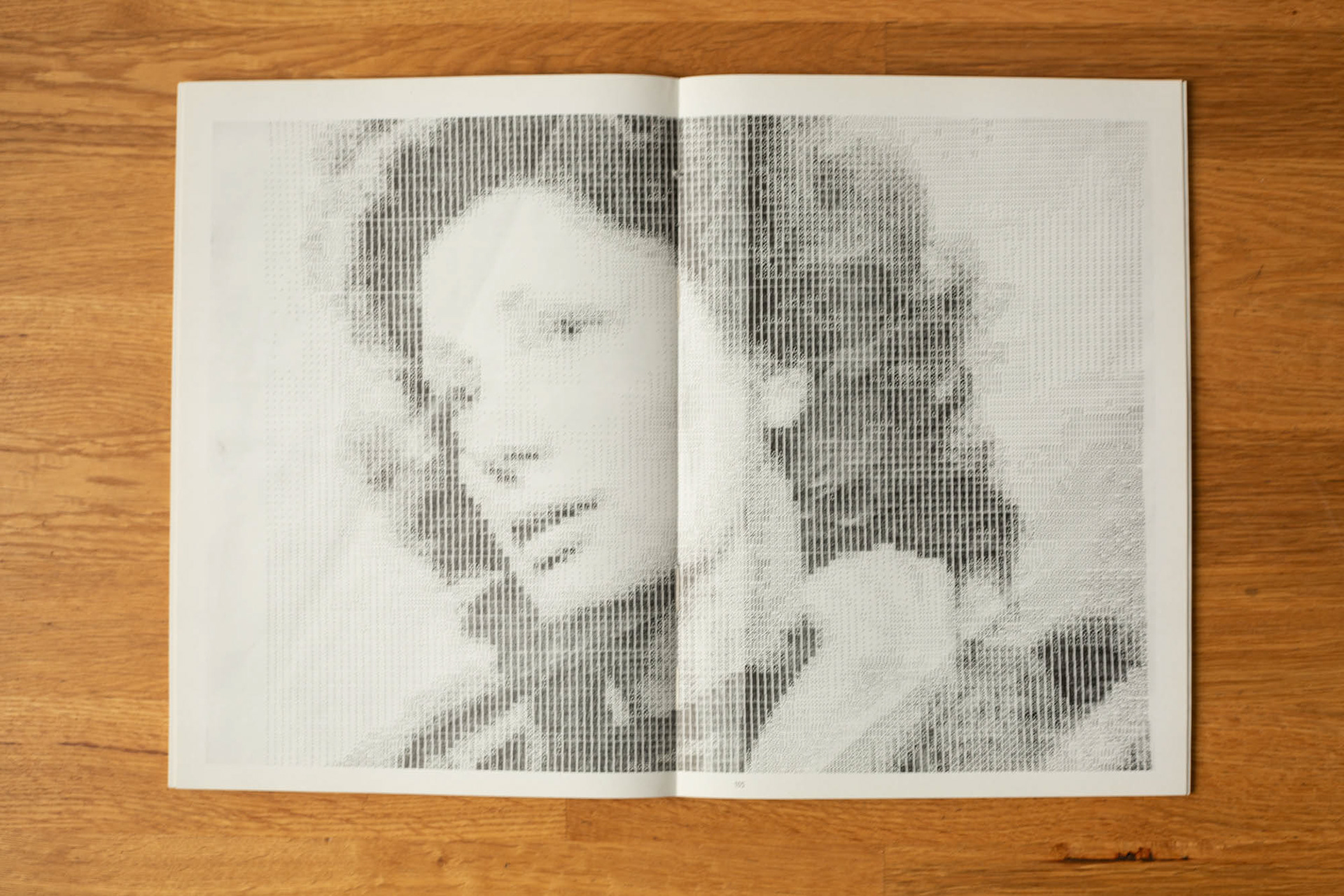

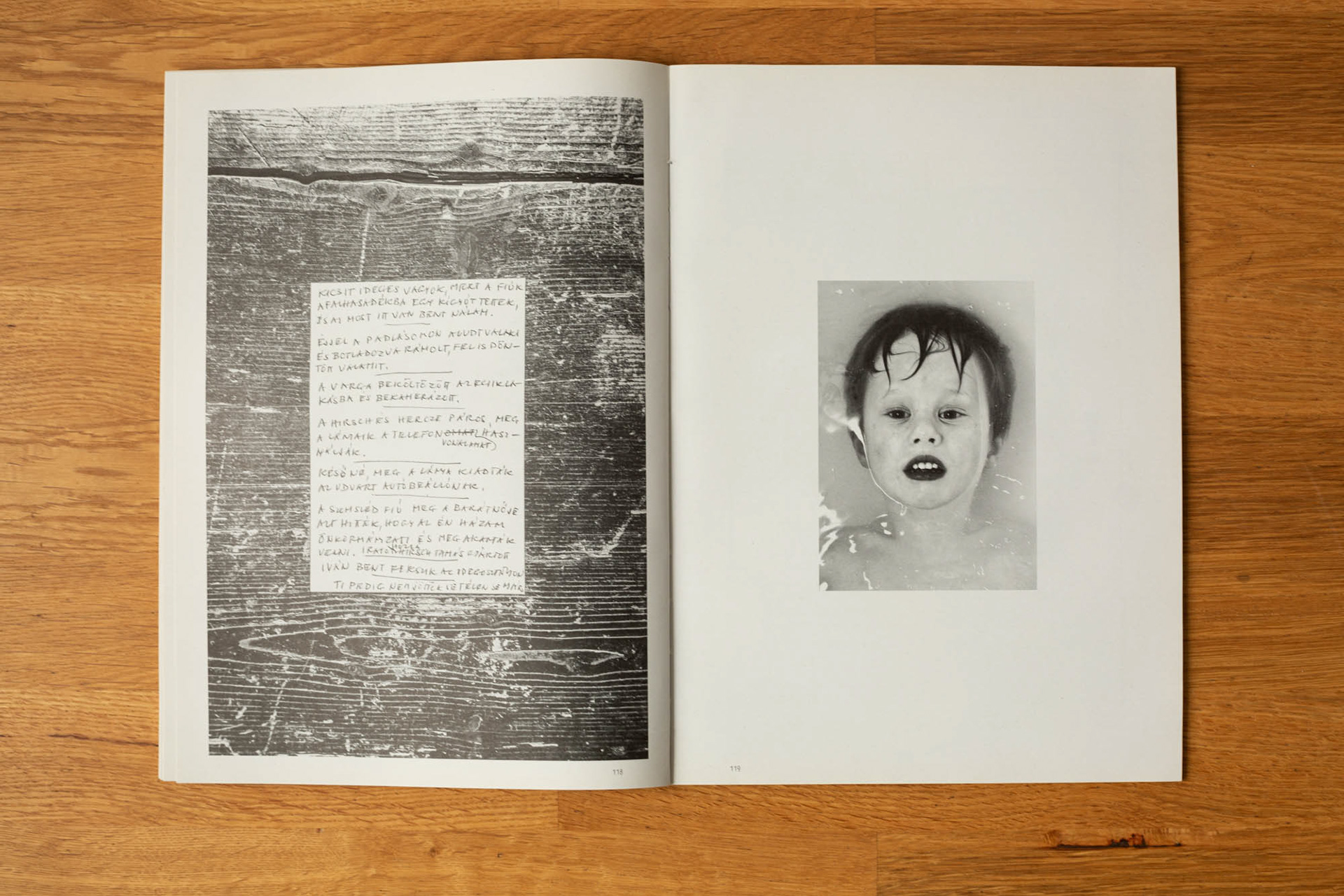

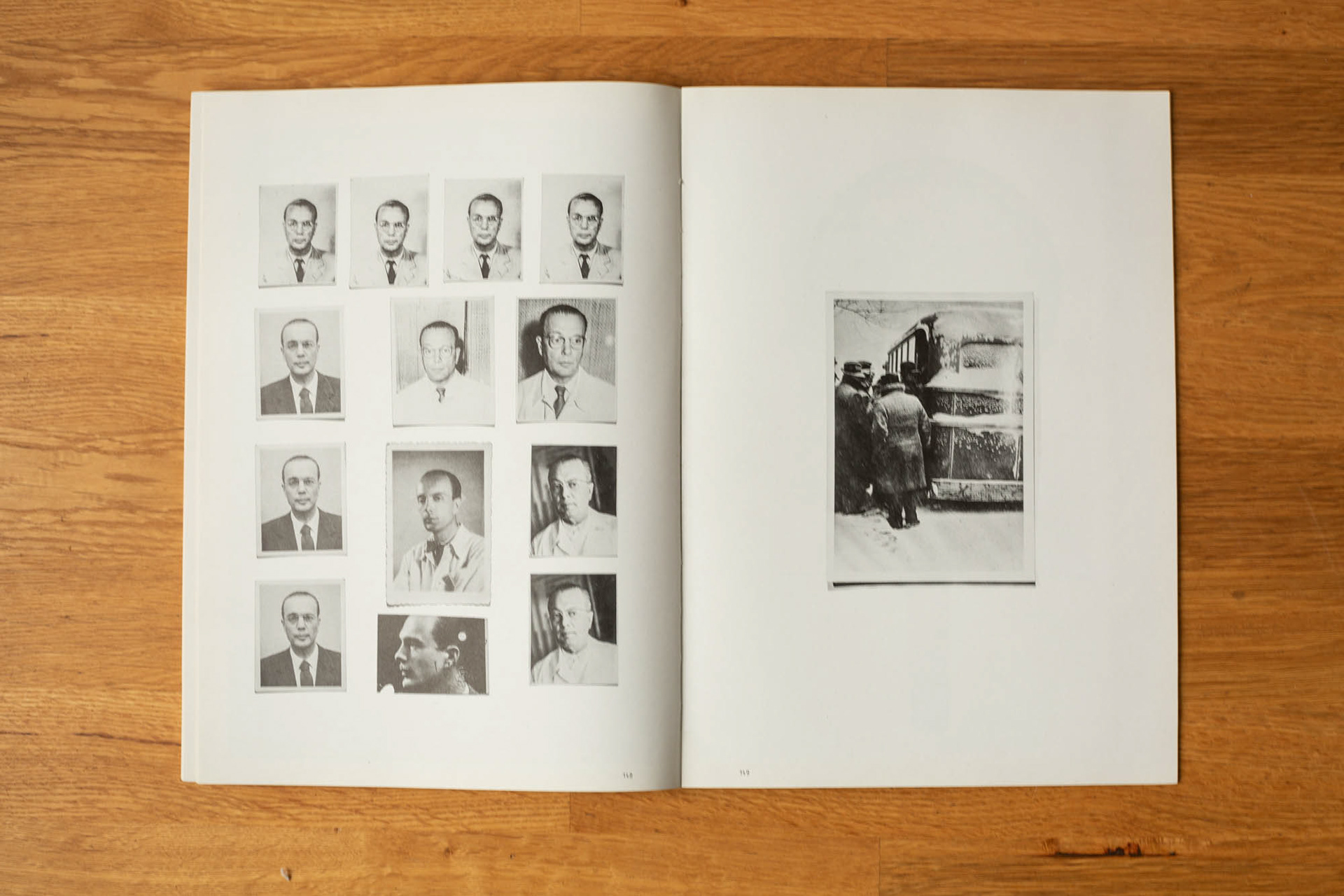

MEMORABILIA 2010-2014 / Painter Emese Kudász died on 22 November, 2010. In the years that followed, her son Gábor Arion Kudász catalogued her entire estate, so as to establish a guide to the workings of memory. The artistic research disrupted the order she had created, something that surrounded her and was distinctively her own. Through the cracks of this disrupted order, hidden aspects of her personality emerged, together with a previously unrealised coherence among her objects; it is no longer possible to tell whether these had existed before or were only the result of the intervention. The structure of the estate itself encouraged the creation of collections as it comprises very individual, occasionally downright extravagant, corpuses forming the backbone of this exhibition and the accompanying book: hundreds of four-leaved clovers pressed between newspaper, wardrobe items kept by seasons and colours, bookshelves, printing blocks of an aged catalogue and endless personal objects, messages from the grave.

The title Memorabilia has an atmosphere more befitting the environment of a classic collection that is evoked by the idea of the inventory book. Its closest kin is the museum inventory, which follows traditional rules in describing, cataloguing and classifying objects. The collection whose inventorying is carried out here has all the resemblance of a curiosity cabinet (wunderkammer or kunstkammer), a form of collection that emerged during the Renaissance and was popular from the 16th to the 18th century. It was common, particularly for aristocratic and big bourgeois families, to dedicate a room or cabinet to things worthy of collection. Representing all and any fields of science, art and life, these assemblages were as likely to feature minerals and miniatures as clever contraptions and book rarities. These curiosity cabinets were home to scientific concepts about the world, the experience of the past, and inferences that could be drawn from objects. Such a collection had personal motivations and faithfully represented the worldview of its owner, as was evident in the act of classification. It was an instrument of inventorying, of interpretation, though not yet in its encyclopaedic form, but in a playful variety.

The order of things according to Memorabilia

a) Personal effects, mostly personal items that bear the warmth of the significant person’s hand, keep her scent, their surface was worn by her gaze. On their own, these objects are often without value and interest; they are not even individual, do not directly refer to their owner — yet an assemblage of mementoes of this kind makes the taste, habits, lifestyle and spirit of the subject of remembrance recognizable.

b) Things considered suitable to be tokens of remembrance, and marked as such. Both the rememberer and the subject of remembrance have agreed to elevate them above similar objects.

c) Real memorabilia, objects for remembrance, mementoes. Articles produced in multiple copies with the express function of serving as triggers of memory, which can be identified with the subject of memory only through an image or name.

The title Memorabilia has an atmosphere more befitting the environment of a classic collection that is evoked by the idea of the inventory book. Its closest kin is the museum inventory, which follows traditional rules in describing, cataloguing and classifying objects. The collection whose inventorying is carried out here has all the resemblance of a curiosity cabinet (wunderkammer or kunstkammer), a form of collection that emerged during the Renaissance and was popular from the 16th to the 18th century. It was common, particularly for aristocratic and big bourgeois families, to dedicate a room or cabinet to things worthy of collection. Representing all and any fields of science, art and life, these assemblages were as likely to feature minerals and miniatures as clever contraptions and book rarities. These curiosity cabinets were home to scientific concepts about the world, the experience of the past, and inferences that could be drawn from objects. Such a collection had personal motivations and faithfully represented the worldview of its owner, as was evident in the act of classification. It was an instrument of inventorying, of interpretation, though not yet in its encyclopaedic form, but in a playful variety.

The order of things according to Memorabilia

a) Personal effects, mostly personal items that bear the warmth of the significant person’s hand, keep her scent, their surface was worn by her gaze. On their own, these objects are often without value and interest; they are not even individual, do not directly refer to their owner — yet an assemblage of mementoes of this kind makes the taste, habits, lifestyle and spirit of the subject of remembrance recognizable.

b) Things considered suitable to be tokens of remembrance, and marked as such. Both the rememberer and the subject of remembrance have agreed to elevate them above similar objects.

c) Real memorabilia, objects for remembrance, mementoes. Articles produced in multiple copies with the express function of serving as triggers of memory, which can be identified with the subject of memory only through an image or name.

WEB

http://www.arionkudasz.com/